Communicating Christ in a Multicultural World

10 Tribal Religions

Lesson Objectives

To understand world religions and how to reach those who follow them with the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

Introduction

Why Study Tribal Religions?

Around the world, people search for God in different ways. In hundreds of cities, towns and villages this search finds expression in local religions, deities, practices and cultures that have not yet been influenced by the major faith systems. In a globalised world, however, tribal religions that would once have been out of the public gaze are now front and centre, as missionaries, anthropologists, international organisations and television crews draw attention to them..

Amid the glass and concrete of our modern Western culture, why should we be concerned with tribal religions?

- to enable us to understand tribal societies (est. 350 m people), including traditional Australian Aboriginal culture, and have an informed Christian response

- tribal worldviews feature largely in Sub-Saharan Africa, the Pacific Islands, Southeast Asia, Siberia, the Americas, India, and indigenous Australia; most predominantly Muslim, Buddhist, Hindu nations also have strong tribal religions, eg Shinto Japan vs Nagano indigenous religion;

- to equip us to reach tribal people in their traditional settings - while many have disappeared in the last hundred years, others remain

- Stephen Neill estimates the tribal worldview is the view of 40% of the world's population, often referred to as "folk religion'

Tribal Societies are "Religious

Many Westerners have assumed people living in tribal societies have no religion. For example, early settlers in Australia looked for established churches, gods, scriptures, hymns, sacrifices, creeds and priests and concluded the Aborigines had no religion, simply because there were no outward signs. Darwin drew the same conclusions after his travels.

Anthropologists (even agnostic ones) now agree almost all societies have some form of religion. In so-called "undeveloped" (including pre-literate) societies the presence and power of religion are more pronounced than in the West. "Religion" in these "holistic" cultures is highly complex; cannot be separated from society as a whole. The whole of life is a religious phenomenon. In some cultures, religious beliefs saturate the language.

May comprise:

- visible forms, eg witchdoctors, shamans, superstitions

- non-visible forms - to outsiders, eg secret rites to some of their own cultures, eg women and children

- non-recognizable forms, eg animism

Many people in tribal societies are dominated by fear of gods, spirits, witches, ancestors, and the forces (including nature) they can unleash against them, eg storms, fire, tsunamis, earthquakes, famines, disease, death. Much of their lives is spent appeasing, avoiding, sacrificing to powers they do not understand.

Christ came to set people free and bring them into the Kingdom of the real God. Case Studies

- llama foetuses in Cochabamba;

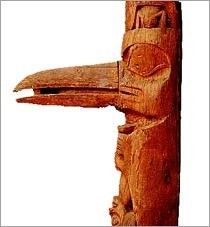

- totems in North American Indian settlements.

- The Chippewa make totems ("ototeman", or "he is my relative") of birds, fish, animals, plants, other natural objects. Totemism: involves beliefs and practices in which relations are postulated between people or groups of people and natural species, objects or phenomena. Not necessarily "worship". The totem links the individual with nature and the past. Some consider totems as ancestors. Clans have rules against killing or eating species to which totems belong. Members are often known by names of totems. Some clans consider totems holy and pray to them;

- Dreamtime - traditional Aboriginal religion.

- Hungry Ghost Month, Singapore

Common Features of Tribal Religions

There are hundreds of variants, but some common features.

1. Strong Awareness of the Spirit World

Tribal people are usually very sensitive to the spiritual realm around them. Assume spirit powers behind everything and every event. Traditional Australian Aboriginals attributed sickness and death (except in very old people) to sorcery; death (even from sickness) was considered unnatural. The key was to establish the source (usually human) of the sorcery; may have been someone outside of the clan, or a clan member who failed to perform their kinship obligations. Among the Mendi of PNG, sorcerers traditionally attribute sickness to supernatural powers manifesting themselves in peoples' bodies. In South Pacific societies strong belief in a life force resident in certain people, called "mana". Referred to by other names in other cultures. Sometimes inhabit charms, rituals, amulets (to ward off spirits) as well as people (eg warriors) and inanimate objects (such as bows and arrows).

Animists (Latin = "spirit") believe nature is populated with spirit beings and that everything is inhabited, "animated" by spiritual forces, including trees, rocks, rivers, mountains, fire, water. Spirits are assumed to be everywhere; some are malevolent, ie evil or tricks on people; others can be appeased with prayers and offerings. Many are identified as demons or evil spirits, inherently evil and contrary to peoples' interests. In some societies. considered to be gods. May enter people's bodies to make their needs or wishes known. This often happens in the religious practices of Southeast Asian folk traditions, where rural people mix religious beliefs and practices with animism. Animists believe that there are good and bad spirits. who cause good and bad fortune. Farmers offer sacrifices to spirits in the hope they will bring good fortune and not harm them. Some farmers build boxes on the tops of poles in their rice paddies, in which they place cloth, food, incense, paper, and special objects.

In some cultures, spirits are believed cause conception; according to Berndt, Aborigines in the Western Desert of Australia did not make a connection between sexual intercourse and conception; believed the latter occurred at sacred waterholes and other sites where the "spirit of barramundi", crocodile, kangaroo, etc entered a mother's body, resulting in birth. Others believed the father "found" the unborn child's spirit in a dream and the infant's totem was determined by the context of the dream.

2. A Supreme God

Most tribal religions believe in a Supreme Being, eg a "Sky God", who is above all other spirit beings. Often regarded as "Creator". Sometimes concerned with peoples' moral lives, decisions, and families. Often overlooked by outsiders if not celebrated in temples, images.

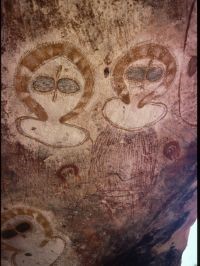

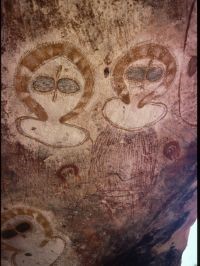

Australian Aborigines did not have divinities as such, but believed in spirit beings (Wandjina a predominant spirit being in Kimberleys).

In North American traditional religion, God is the "owner" of animals, who cares for them as the Great Spirit cares for men. As Paul discovered (Acts 17), He may not be recognizable. Lunda for God = "God of the Unknown"; "Ngombe = "the Unexplainable"; Maasai = "the Unknown". Sometimes too far away, reachable only through inferior spirit beings.

3. Living Dead (Ancestors)

Believe the spirits of those who die live on and have contact with those who remain. The living must honour them. In some societies, witchdoctors and other specialists are employed to get rid of them, including through elaborate funerary rituals. In other cultures, ancestors are seen as vital links between the living and the spirit world, so their services are sought, eg to help with the harvest, protect from evil beings, ensure fertility. Ancestors may be worshipped, feared or simply remembered. Shrinking of heads linked in some cultures to ancestors. May inhabit mediums.

4. Myths

"Myth" has a specific anthropological meaning:

- a sacred narrative that expresses the unobservable realities of religious belief in terms of observable phenomena.

Tribal societies typically not literate (at least in their own languages), so little written apart from (often flawed) anthropological records. Many are pre-literate and word of mouth (oral tradition) is the main form of communication.

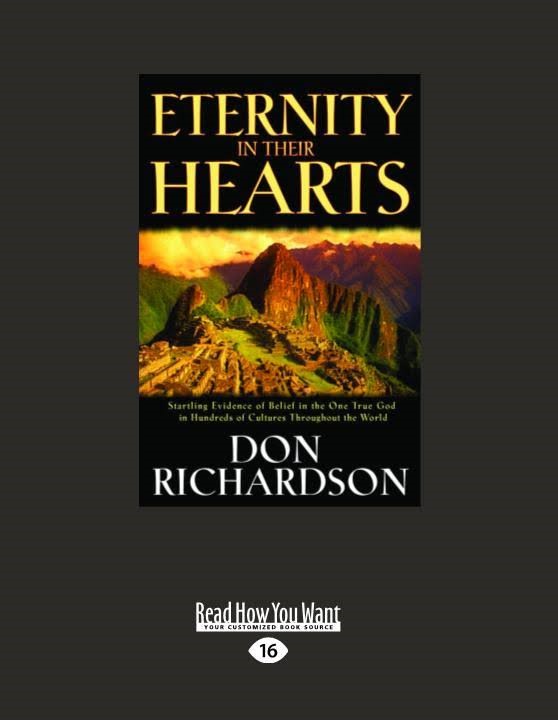

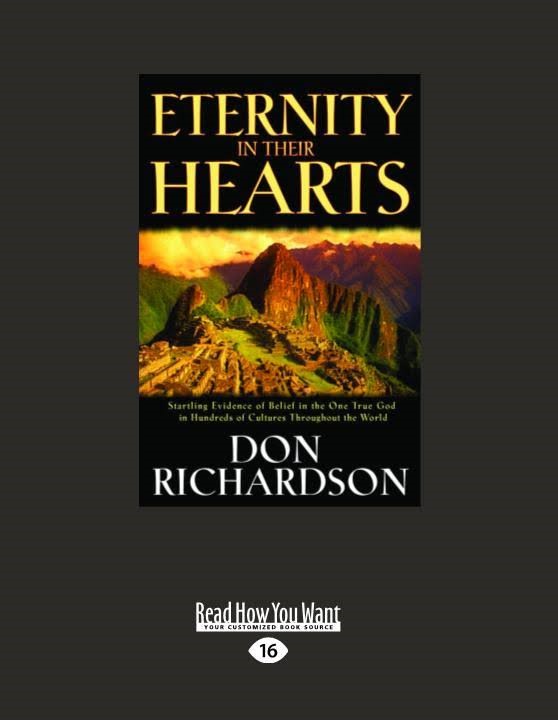

Tribal myths often start with the beginning of all things (not necessarily called "creation"; one of the characteristics of the Dreamtime is that it does not point to a specific creation act, although the concept of creation exists throughout). Some common features, eg Eskimo (Innuit), Central American and Oceanic accounts of a great flood, with a hero who saved a remnant). Richardson's Eternity in their Hearts cites many examples of stories that echo Biblical accounts; suggests this is because their prehistory recalls the revelation of God.

Art, rock paintings, headdress, sculpture, etc are used to depict beliefs. (In the Middle Ages stained glass windows had a similar function in Europe.) Myths define why sites are "sacred"

5. Dreams and Visions

The cosmos is believed to be two-dimensional. Individuals, eg priests, shamans believed to have special powers or abilities to relate to the spirit world, by possession, revelation, trances, ecstasy. Dreams and visions (and their interpretation or divination) assume greater importance, eg as communications of the gods, ancestors, and spirits, or as guides.

6. Sacrifices and Other Rituals

Prayers and offerings feature strongly. Many tribal societies have elaborate systems of sacrifice, including animals and crops (and, previously, people). In some traditional cultures, cannibalism was practiced for religious reasons, eg to imbibe the spiritual strength of a warrior enemy, not for nutrition (cf Captain Cook). Rites of initiation, birth, puberty, marriage, war, sickness, divorce, eating, cooking, planting, reaping, herding, house-building, departing and arriving, buying, selling, purification or burial.

7. Specialists

Tribal religions utilise the services of specialists, eg medicine men, diviners, seers, priests, mediums, shamans, healers, magicians. These look after shrines and totems, organise rites (their "work"), proclaim the will of the gods, and provide guidance, eg hunting, agriculture, acquisition of wives, naming of children, places of residence. Often chosen at birth.

The word "shaman " comes from Tungus of Siberia; describes a religious personage who cures sickness, directs communal sacrifices, escorts the souls of the dead to the other world, "visits" distant places in spirit (cf astral travelling), has ecstatic experiences, divines the spiritual dimension and ensures protection.

In Aymara communities in Bolivia, curers exercise supernatural power to heal sickness, control natural phenomena, overcome personal difficulties, and produce good crops. Shaman midwives read coca leaves to divine the gender of unborn children. People expect magic to work.

"Fear" is common, eg fear that sorcerers can hasten death, cause hail to destroy maturing crops, fire to consume a house, relationships to disintegrate.

In Aboriginal culture, "pointing the bone" was the most common form of sorcery. A specially prepared bone was pointed at a victim in a pointing rite. Men with special powers would "sing" a man to death; sometimes hundreds of kilometres away. The aim was to cause death by separating the spirit from the body. Either the spirit of the bone was believed to enter the victim or the victim's soul was captured by the bone. Death was inevitable.

The fear of having one's spirit captured is widespread, cf Aymara at San Pedro, Lake Titicaca. Fear of night, of witches, of angry (or vengeful) ancestors. Shamans are expected to allay those fears by dealing with the forces.

8. Taboos

Notions of "Tabu" (from Polynesian word meaning, "what is prohibited") are common in tribal religions, eg things that may not be eaten, touched or seen, or only by sacred persons such as chiefs or priests, or by only one gender. In many societies sex, birth, menstruation, death are associated with taboos, regulations and sanctions. Some taboos result in exclusion from society, or worse. Taboos vary enormously between clans.

Why Do Witchcraft, Magic and Sorcery Appear to Work?

Why do they obtain desired results under particular circumstances?

- they meet the spiritual search of participants;

- meet psychological needs; "Magic is a pseudo-science in which adherents believe a cause-effect relationship exists between magical acts and desired events" (Tylor);

- people expect it to work;

- politically correct to do so; witchdoctors are often senior members of village/tribal hierarchy and enjoy social status; people feel diffident in their presence and assume their activities are bona fide;

- practitioners are simply expert observers of natural phenomena, eg weather cycles, habits of fauna, knowledge of arranged relationships ("love magic");

- reaffirm particular teleologies, eg by explaining the cosmos, unexplained events (such as sickness, death), providing scapegoats in time of disaster;

- failure would place the social system in doubt;

- spiritual powers are real and produce real results, including healings, resurrections;

- fraud.

Traditional Aboriginal Religion

Aboriginal society was not animistic but totemistic.

Traditional Aboriginal Religion is rich and diverse, but complex.

Early settlers believed the Aboriginals had no religion. In fact, tribes shared a fairly common view of the world (by definition, not a Western view) and its relationship to the Dreamtime.

Modern acceptance by churches of the Dreamtime as a validation or explanation of Aboriginal "attachment to the land" miss the underlying issue, as far as Biblical response is concerned. The primary relationship of Aboriginal people to the land (or "country") was religious and symbolic.

Aborigines believed the land was originally formed by ancestral beings who followed certain tracks as they travelled through the countryside during "the Dreamtime", giving it life and form, providing physical manifestations of their passage as distinguishable parts of the landscape. Coolum and Maroochy are myths.

These supernatural beings (who are still there, but are no longer visible) determined who should be custodians (not "owners") of the land by bestowing it on human beings whom they named. Aborigines regarded the land as their spiritual home ("that rock my father; earth my mother"), the locality of their totems the locus of the clan spirit.

Aboriginals are aware of the idea of idea of creation. "Dreamtime" was when it all began, in prehistory. The landscape as we know it assumed its shape at that "time". Ancestral beings took the forms of kangaroo-men, emu-men, bower-bird-women, etc. Clans had sacred site/s, important for totemic reasons.

In some cultures reality (including literal acceptance of other human beings) was based on totemic identity. Totemism gave people reality/identity, brought them together to celebrate community/clan.

Stories found their way into song. Older men handed down traditions (there were usually several layers of meaning). Message boards, message sticks, cave paintings, carved rocks also held secrets).

Activities of the Dreamtime were re-enacted in corroborees, complete with didgeridoo songs, body paintings, sand sculptures, dances. Some were restricted along gender lines, as was access to major sacred sites. Some related to rites of passage, eg circumcision, sub-incision, scarification, tooth avulsion, death. Rites also used to attract food supplies and rain, ritually purify, and in funerary and burial ceremonies. The Dreamtime is believed to be part of the present: man participates in it by observing the rituals the Dreamtime Beings established and in which they still manifest themselves, in the forms of human actors. They were stewards of the land as long as required ceremonies were carried out.

Aboriginal reality is defined by the spiritual dimension. Aboriginal men believe they have the spirits of their "totems" that live in water holes, rocks, totem animals and plants. Much closer to nature than Westerners.

Yolngu in Arnhem Land related magic to hunting, food collection, fishing, control of the weather, human emotions, healing, psychological change and success in inter-tribal conflict. Using "healing stones", the Marrnggitj claimed to be aided by "familiar spirits" only visible to them. Believed in Galka, who were able to punish people who breached taboos.

The impact of (predominantly British) settlers on the land and its people was disruptive. The first 150 years of European settlement marked by fundamental clash of worldviews and cultures that is still not appreciated.

Syncretism is common: "Yolngu often pray to God and then consult the witchdoctor".

Christian Responses

- spend substantial time with them and establish trust to recognise their spirituality (as did Paul in Athens), without being side-tracked, then...

- provide Christian teleology, ie explanation of the world, conditions;

- explain the nature of sin and God's redemptive purposes;

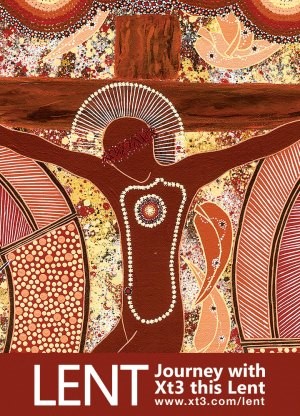

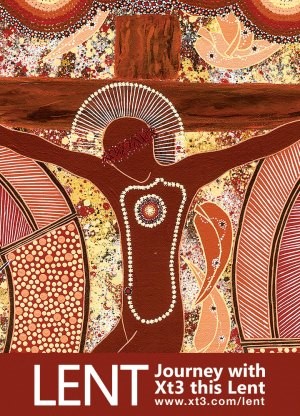

- understand the culture and how to "incarnate" the Gospel in its forms, language, etc, (eg Aboriginal "attachment" to land and notion of desecration of sacred sites closer to Hebrew than to Greek thought);

- recognise "shadows" of divine revelation, eg John Rudder "inside out");

- acknowledge and respect parts of the culture that have nothing to do with the Gospel (eg authority structures - who says the Western way is better anyway?

- don't confuse evangelism with being a missionary for Western culture);

- recognise traditional barriers and resentments, including those created by colonial history;

- "translate" the Gospel, eg the Fall of Man, lost sheep, Lamb of God, "whiter than the snow" ;

- practice the presence and love of God;

- love Jesus Christ passionately and let it be seen;

- understand and avoid syncretism;

- reveal the One True God, His character and attributes as the object of their search;

- operate in the power of the Holy Spirit - in a tribal situation Power Encounter often precedes Truth Encounter, (ie what can the Christ God do?);

- address issues that cause fear, eg spirit world, guilt (Christians do not fear evil spirits, divine retribution, because God's love casts it out, I John 4:18); pray and plan for People Movements.

Eternity is in their hearts.